|

i

School

Days and Preschool Days, Too:

A treasury of anecdotes culled from my work

and play as a preschool worker and an elementary school after- school

activities supervisor

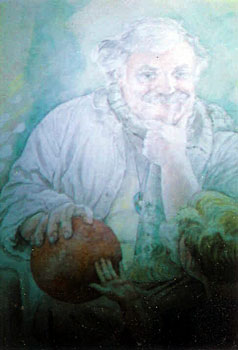

painting

by Diane Cobb, reprinted with permission

2003 portrait of the author at work with

a child, by artist/art teacher, Diane Cobb.

INTRODUCTION

I

wrote the vignettes on the following pages while working

at a California private school for preschool through fifth grade children.

Currently, I'm a full-time preschool teacher. For three years beginning

in January, 2001, though, I spent weekday afternoons as an after-school

activities supervisor for elementary schoolers. I've also substitute-taught

in all grades.

At times I'm scarcely

able to wait till I can write down the hilarious or otherwise amazing

words I hear and the sights I see. I wouldn't be able to imagine scenes

so touching or funny.

Of course, working with young

children is demanding. Most of our teachers are exhausted by day's end.

The work calls into play our most adult qualities, and our most childlike.

A preschool teacher learns

early on that two to five year-olds do not share a grown-up's perception

of time or the world. This situation can make for humor, as well as

confusion. A little girl, for example, once told me her parents were

going away.

"Oh?" I replied, as much in

as a musical call-and-response as anything. "How long are they

going for?"

"Forty days!" she exclaimed

with wide, distressed eyes. Her mother's eyes got a little wide, too,

when I shared what her daughter had told me.

"We're going to Sonoma for the weekend,"

she said. "Betsy's going to sleep at her grandma's one." That

wasn't how it felt to Betsy.

Another little girl announced excitedly

one day, "I'm not going to be at this school any more, after today!"

When she showed up the next day, and the day after that, I asked her

dad when they were moving.

"Oh, we're not moving," he

said. "We're going to Hawaii, but not for another week. And we'll

be back a week after that."

As far as geography goes, many little

ones know a place called Disneyland. Beyond that, understanding is often

very sketchy. When a child comes back from a long trip and the teacher

asks, "Where did you go?" the boy or girl is likely to say,

"On an airplane", end of story. A similar mix-up occurs when

a child gets injured. The question "where did you hurt yourself?"

almost always brings an answer like "over by the sliding board".

Nowadays I always phrase my exploratory question, "What part of

your body did you hurt?"

Because the consciousness of a small child

is so much in its own world, calling on people who spontaneously raise

their hands at Circle--even though "a quiet hand" is just

what we ask for, if someone wants to speak--can bring unexpected results.

One boy's comment, no matter what the ongoing class topic was, always

focused on cars. Another boy would begin with a statement tangentially

connected to the classroom discussion. Using the phrase "and then",

would segue in breathtaking leaps to a narration of his entire life

history, all told with vague pronoun references in Faulknerian stream-of-consciousness.

The teacher would smile and nod, listening long enough to validate the

boy, and. then politely move on to the next song.

Socialization is one of the main themes,

and probably the major subtext, of our little preschool community. Research

shows that most children have to be around four before they begin to

recognize reciprocity and the rights of others. We have many two and

three year-olds in our play yard, so that seeing someone grab a toy

from someone else--maybe even bop the other child on the head with it--and

justify the act later with "But I wanted it!" is not

an uncommon experience. Desire is in fact

the most frequent justification of lots of things. "You need to

put that toy away now, it's lunch time" brings the reply "But

I want it!". If the child was a lawyer, he'd follow that

statement with "I rest my case" and feel confident about the

verdict. Moving out of the narcissism of early childhood is a long and

difficult process.

I knew a three-year-old recently who volunteered

to get a wet kleenex for someone who'd gotten sand in an eye. Afterwards,

the boy explained his action without my asking: "I've had sand

in my eye before, Mr. Max, so I knew how Albert was feeling."

Such maturity is as heart-warming as it is unusual.

Another boy demonstrated a rare quality

when I gave him a "time out" for hitting someone. Time outs

are very short at our school, and after thirty seconds or a minute I

nodded at him and said, "OK, Randy." Some twenty minutes after

that, it was time to go inside. Randy, still sitting next to the wall

of the building, said, "Mr. Max, may I get up from my time out

now?" He hadn't realized my "OK" meant "it's OK

to get up and play", and had sat there for twenty minutes out of

simple loyalty, believing himself to be still atoning for his little

infraction. I apologized profusely for not having been more clear.

Discipline for all our children is based

on the work of Howard Glasser, author of "Transforming the Difficult

Child", a book whose principles really apply to everyone. We try

to give children ample praise and to use brief time-outs, administered

without anger, when they are necessary.

The teacher's eternal dilemma, of course,

is what to do when you came upon a situation just after it happened.

Sometimes a young bystander will believably recount what she saw. Asking

the participants usually brings complications. "What did you do

to Ellen?" usually brings a passionate narration of "what

Ellen did to me!" One of my friends told me once, "Even

King Solomon wouldn't be able to sort out all this.!" We try our

best, though, to be fair and kind.

After awhile I felt I'd met my Waterloo

in the after school program with the elementary school boys and girls.

My efforts to encourage boys to "lighten up" about their competitiveness

in sports met grim resistance. My suggestions of funny team names like

the "San Francisco Sweatsocks" brought the kind of silence

one might expect from flatulence at the Queen's tea party, followed

by renewed calls of "We're the Giants!" "No, we're

the Giants!" "OK, we're the A's!"

Since I began writing these stories down,

our play yard has changed considerably, a consequence of the ever-rising

insurance cost and ever more prevalent threat of lawsuits that schools

face. The low, metal bars I describe catching children jumping off are

gone now, as is the platform from which one boy used to proclaim, "I'm

so high!" Children are no longer allowed to climb the practically

banzai juniper tree, though fortunately they may still swing from a

branch. Nor am I allowed any longer to hold people's hands for leverage

as they swing easy backward somersaults. Someone's shoulder got dislocated

elsewhere in the school in a different activity. But we can't be too

careful. They can do somersaults with their dads, I tell them, and their

parents may bring them to the yard on weekends if they want to climb

the tree.

All that just means we have to use our

imaginations more. Fortunately, imagination is nearly boundless, and

is close at hand for children. Something magical nearly always still

happens when I enter their lilliputian world.

*****

continued back contents title

page

"What Remains Is

the Essence", the home pages of Max Reif:

poetry, children's

stories, "The

Hall of Famous Jokes", whimsical

prose, paintings, spiritual

recollection, and much more!

Enjoy

the stories? Have any of your own ?

Please introduce yourself:

send an e-mail

my way

or

sign my Guestbook

|